Doubling battery power of consumer electronics

New lithium metal batteries could make smartphones, drones, and electric cars last twice as long.

Rob Matheson | MIT News Office

August 16, 2016

An MIT spinout is preparing to commercialize a novel rechargeable lithium metal battery that offers double the energy capacity of the lithium ion batteries that power many of today’s consumer electronics.

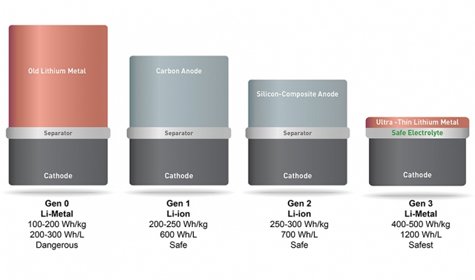

Founded in 2012 by MIT alumnus and former postdoc Qichao Hu ’07, SolidEnergy Systems has developed an “anode-free” lithium metal battery with several material advances that make it twice as energy-dense, yet just as safe and long-lasting as the lithium ion batteries used in smartphones, electric cars, wearables, drones, and other devices.

“With two-times the energy density, we can make a battery half the size, but that still lasts the same amount of time, as a lithium ion battery. Or we can make a battery the same size as a lithium ion battery, but now it will last twice as long,” says Hu, who co-invented the battery at MIT and is now CEO of SolidEnergy.

The battery essentially swaps out a common battery anode material, graphite, for very thin, high-energy lithium-metal foil, which can hold more ions — and, therefore, provide more energy capacity. Chemical modifications to the electrolyte also make the typically short-lived and volatile lithium metal batteries rechargeable and safer to use. Moreover, the batteries are made using existing lithium ion manufacturing equipment, which makes them scalable.

In October 2015, SolidEnergy demonstrated the first-ever working prototype of a rechargeable lithium metal smartphone battery with double energy density, which earned them more than $12 million from investors. At half the size of the lithium ion battery used in an iPhone 6, it offers 2.0 amp hours, compared with the lithium ion battery’s 1.8 amp hours.

SolidEnergy plans to bring the batteries to smartphones and wearables in early 2017, and to electric cars in 2018. But the first application will be drones, coming this November. “Several customers are using drones and balloons to provide free Internet to the developing world, and to survey for disaster relief,” Hu says. “It’s a very exciting and noble application.”

Putting these new batteries in electric vehicles as well could represent “a huge societal impact,” Hu says: “Industry standard is that electric vehicles need to go at least 200 miles on a single charge. We can make the battery half the size and half the weight, and it will travel the same distance, or we can make it the same size and same weight, and now it will go 400 miles on a single charge.”

Tweaking the “holy grail” of batteries

Researchers have for decades sought to make rechargeable lithium metal batteries, because of their greater energy capacity, but to no avail. “It is kind of the holy grail for batteries,” Hu says.

Lithium metal, for one, reacts poorly with the battery’s electrolyte — a liquid that conducts ions between the cathode (positive electrode) and the anode (negative electrode) — and forms compounds that increase resistance in the battery and reduce cycle life. This reaction also creates mossy lithium metal bumps, called dendrites, on the anode, which lead to short circuits, generating high heat that ignites the flammable electrolyte, and making the batteries generally nonrechargable.

Measures taken to make the batteries safer come at the cost of the battery’s energy performance, such as switching out the liquid electrolyte with a poorly conductive solid polymer electrolyte that must be heated at high temperatures to work, or with an inorganic electrolyte that is difficult to scale up.

While working as a postdoc in the group of MIT professor Donald Sadoway, a well-known battery researcher who has developed several molten salt and liquid metal batteries, Hu helped make several key design and material advancements in lithium metal batteries, which became the foundation of SolidEnergy’s technology.

One innovation was using an ultrathin lithium metal foil for the anode, which is about one-fifth the thickness of a traditional lithium metal anode, and several times thinner and lighter than traditional graphite, carbon, or silicon anodes. That shrunk the battery size by half.

But there was still a major setback: The battery only worked at 80 degrees Celsius or higher. “That was a showstopper,” Hu says. “If the battery doesn’t work at room temperature, then the commercial applications are limited.”

So Hu developed a solid and liquid hybrid electrolyte solution. He coated the lithium metal foil with a thin solid electrolyte that doesn’t need to be heated to function. He also created a novel quasi-ionic liquid electrolyte that isn’t flammable, and has additional chemical modifications to the separator and cell design to stop it from negatively reacting with the lithium metal.

The end result was a battery with energy-capacity perks of lithium metal batteries, but with the safety and longevity features of lithium ion batteries that can operate at room temperature. “Combining the solid coating and new high-efficiency ionic liquid materials was the basis for SolidEnergy on the technology side,” Hu says.

Blessing in disguise

On the business side, Hu frequented the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship to gain valuable insight from mentors and investors. He also enrolled in Course 15.366 (Energy Ventures), where he formed a team to develop a business plan around the new battery.

With their business plan, the team won the first-place prize at the MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition’s Accelerator Contest, and was a finalist in the MIT Clean Energy Prize. After that, the team represented MIT at the national Clean Energy Prize competition held at the White House, where they placed second.

In late 2012, Hu was gearing up to launch SolidEnergy, when A123 Systems, the well-known MIT spinout developing advanced lithium ion batteries, filed for bankruptcy. The landscape didn’t look good for battery companies. “I didn’t think my company was doomed, I just thought my company would never even get started,” Hu says.

But this was somewhat of a blessing in disguise: Through Hu’s MIT connections, SolidEnergy was able to use the A123’s then-idle facilities in Waltham — which included dry and clean rooms, and manufacturing equipment — to prototype. When A123 was acquired by Wanxiang Group in 2013, SolidEnergy signed a collaboration agreement to continue using A123’s resources.

At A123, SolidEnergy was forced to prototype with existing lithium ion manufacturing equipment — which, ultimately, led the startup to design novel, but commercially practical, batteries. Battery companies with new material innovations often develop new manufacturing processes around new materials, which are not practical and sometimes not scalable, Hu says. “But we were forced to use materials that can be implemented into the existing manufacturing line,” he says. “By starting with this real-world manufacturing perspective and building real-world batteries, we were able to understand what materials worked in those processes, and then work backwards to design new materials.”

After three years of sharing A123’s space in Waltham, SolidEnergy this month moved its headquarters to a brand new, state-of-the-art pilot facility in Woburn that’s 10 times larger — and “can house the wings of a Boeing 747” Hu says — with aims of ramping up production for their November launch.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News: http://news.mit.edu/