Imagine you’re driving for Uber or Lyft. As an independent contractor, you enjoy setting your own work hours, picking up people you like chatting with (well, for the most part), learning about new parts of town, and earning back some of the investment in your car. Then, one day, an email from your ride-sharing service informs you that some bureaucrats you’ve never heard of have decided that Uber is now your employer. You have to work a certain number of hours and within prescribed times, and the company will start withholding a portion of your pay for taxes, like a typical paycheck. More changes are probably coming. What do you do?

That’s the dilemma ridesharing drivers may soon be facing if the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Wage and Hour Division follows through on its stated intention to radically redefine what constitutes an employment contract. Ridesharing companies and other sharing-economy startups have operated somewhat freely thanks to the DOL’s relatively laissez-faire attitude toward contracting and other innovative work arrangements. All of that may soon change.

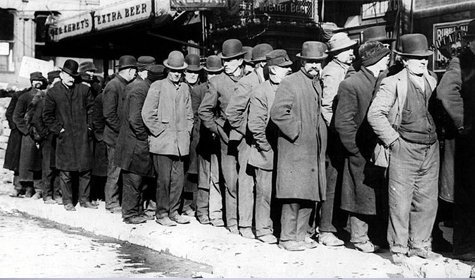

The Wage and Hour Division is, for all intents and purposes, the nation’s wage regulator. In a blog post last July, its head, David Weil, issued new guidance regarding what makes someone an employee rather than an independent contractor. The guidance relies on the expansive wording of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which President Franklin Roosevelt regarded as one of the most important parts of his New Deal.

That act defines employment as simply including “to suffer or permit to work,” giving the Department of Labor huge discretion in defining the term for practical purposes. The New Deal Congress, in choosing this language, specifically rejected the old common law definition of a “master-servant” relationship.

Historically, employment law has centered around that medieval concept (literally in this case) of a master directing a servant, who was seen to have no free will in employment matters. That’s why the employer is liable for an employee’s mistakes. The FLSA, however, goes far beyond this common-law definition, potentially establishing an employment relationship between two freely contracting parties. That has significant implications in a time when the contract is coming back into relevance for large numbers of workers.

The new guidance doesn’t completely gut independent contracting, given that it doesn’t categorize your plumber as your employee, but it significantly reduces the opportunities for independent or contingent work.

The biggest change is a new reliance on “economic dependence,” meaning that if you only work for one company, then it’s likely that the DOL considers you an employee rather than a contractor. That’s true even if your work hours are minimal — if you’re a college student driving for Uber to earn some extra spending money, for example.

The interpretation also states, “A true independent contractor’s work … is unlikely to be integral to the employer’s business.” That is nonsensical. Many small firms contract important functions out to other small firms or individuals, such as graphic design or copywriting work for a small ad agency. Businesses will be forced to bring these functions back in-house, and at greater cost — a considerable burden for fledgling firms.

This redefinition is part of a concerted attempt by the administration to turn back the clock on employment practices to the 1930s, when our governing employment laws were written. The administration in general and Weil in particular want to end innovations in working arrangements, which they claim have led to a “fissured workplace.”

Weil illustrates:

For example, when you walk into the lobby of a hotel these days operating under a well-known brand name, there’s a high probability that the workers who greet you at the desk or clean your room are likely not employed by the hotel chain of that corporate brand. Instead, the management of that hotel property has actually been contracted out to another business offering this service. In fact, many more of the services provided on site — cleaning companies, landscapers, food service providers, etc. — have also been contracted out to providers of these services.

Weil fails to understand how and why firms decide to perform some of these functions in-house in the first place — and why they might outsource others. At about the same time as FDR was pushing through his New Deal, economist Ronald Coase published his classic 1937 article, “The Nature of the Firm,” in which he showed that firms come into being when an entrepreneur hires somebody to perform a service, rather than contract out the task.

Why hire? Coase’s answer was that doing so lowers transaction costs (or as he called them, marketing costs). For example, rather than seeking out a new carpenter every time you need a cabinet built to sell, you can simply hire one as a full-time employee.

In other words, the “fissured workplace” was the norm before the development of the firm, which did things better. So why have we been reverting to the pre-firm model? The reason is simple: the changing nature of transaction costs.

Hiring someone as an employee is not cost-free. At the very least, companies have to pay wages and offer vacation time. And in recent years, the transaction costs of hiring someone have been increasing. Laws like the FLSA impose such requirements as a minimum wage, maximum work week, and overtime. More recently, Obamacare has imposed significant extra burdens on businesses hiring someone to work 30 hours or more a week.

At the same time, the transaction costs of contracting have been decreasing. New technologies reduce the time necessary to find the contractor and reduce the risk of retaining the wrong contractor by enabling instant feedback by all parties in a transaction. That’s what Uber does so well — its smartphone app answers instantly when you ask it whether there is a driver and car for hire in the neighborhood, and tells you how polite and efficient that driver is.

For an entrepreneur launching a business today, it might make more sense to contract out some services, rather than hire new employees and put them on the payroll. The trouble for the DOL is that transaction costs for many job functions have been lowered so much that the 1938 FLSA’s definition of employment no longer applies. Instead, it is forcing people into large firms and strict employment terms and conditions they no longer find valuable.

The world has changed since the 1930s. Independent contractors are no longer victimized by less pay, few benefits, and a denial of the right to organize. In many cases, people choose contract work because of the flexibility it affords. Moreover, being forced into a full-time job comes with its own opportunity costs, as businesses reduce hiring in response to the increased costs that come with every new employee.

The sharing economy has boomed precisely because of these changes in transaction costs for businesses and individuals. By attempting to apply rules formulated during fundamentally different economic circumstances, the Department of Labor could kill off a new avenue of economic opportunity — and kill off the jobs that businesses want to offer and that people want to take.

This article originally appeared at FEE.org at: http://fee.org/freeman/depression-era-laws-threaten-the-sharing-economy/