Boston Globe – THE GREAT state of Minnesota, you’ll be glad to learn, is no longer interested in the size and color of your bug deflector. The legislature in St. Paul recently scrapped the 1953 law regulating that automotive accessory, one of almost 1,200 antiquated or bizarre laws that Governor Mark Dayton recommended repealing as part of a major legislative “unsession.” Among other changes: Minnesotans have been liberated from the ban on possessing more than two hen pheasants, the penalty for distributing berries in the wrong-sized container is history, and it is now legal to coast with your car’s gears in neutral.

“We got rid of all the silly laws,” one state official told the St. Paul Pioneer-Press. That was probably overstating things, given the more than 46,000 laws that Minnesota lawmakers have enacted over the years. Still, the pruning of 1,200 pieces of deadwood is no small achievement.

It’s also a reminder of why nearly all laws and regulations should come with expiration dates.

Politicians are always under pressure to respond to the crisis or controversy of the moment — by passing a statute, imposing a mandate, authorizing a subsidy, setting up an agency. When the issue fades, the laws and regulations remain, long after public attention has moved on.

Over time, some laws become harmless curiosities, like the Massachusetts law doubling the penalty for anyone who picks mayflowers “secretly in the nighttime.” But others — such as the Bay State’s Blue Laws, which still make it illegal to conduct “any manner of labor, business, or work” on Sunday, apart from specified exemptions — continue to affect public policy long after the circumstances giving rise to them have changed.

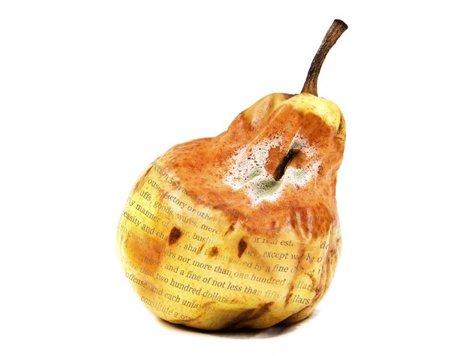

In the real world, things don’t last forever. The carton of milk in your refrigerator has an expiration date. So does the credit card in your wallet. Cars need periodic tune-ups. Medical prescriptions have to be reauthorized.

Government should operate on the same assumption. Every law should expire automatically after a fixed period of time — say, 12 or 15 years — unless lawmakers expressly vote to reauthorize it. Likewise every legislatively created agency and program. Members of Congress and state legislatures should be required to revisit their handiwork on a regular basis, reviewing it for relevance, efficacy, and soundness, and allowing measures that have outlived their usefulness to lapse.

“The presumption should be that laws are experimental solutions to social problems we want to eliminate,” says political scientist Matthew Franck of the Witherspoon Institute in Princeton, N.J. If the solutions are working and continue to be needed, a legislature is always free to extend them. But if the experiments fail — the “solutions” didn’t solve — “a sunset provision helps forestall the problem of vested interests, in and out of government, building up to protect [laws] despite their failure or irrelevance.”

Mandatory sunset clauses aren’t a new idea; American reformers going back to the founders have championed the idea. So numerous and ingrained are the impediments to good government, wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1789, that it should be clear “to every practical man that a law of limited duration is much more manageable than one which needs a repeal.” Congress has sometimes included sunset provisions in federal laws. The post-Watergate independent-counsel statute expired in 1999. The federal assault weapons ban, enacted in 1994 with a 10-year lifespan, lapsed on schedule in 2004. Even when expiration dates are just moved back, as with provisions of the Patriot Act or the Bush-era tax cuts, they at least force lawmakers to debate whether an existing law should be continued.

But ad hoc sunsetting won’t change the underlying assumption that government enactments are forever. It’s this assumption, and the political culture it drives, that makes it so hard to overhaul regulatory codes or streamline government programs.

The key to reform is to flip the assumption that a law once passed lives on in perpetuity. Regrettably, “unsessions” like Dayton’s are all too rare; no such thing has occurred in Massachusetts in recent memory. There have been occasionalefforts in Congress to tackle the problem: In the late 1970s, for example, Senator Ed Muskie of Maine sponsored a bill that would have sunset most federal programs after 10 years. Though it had bipartisan supporters ranging from Barry Goldwater to Ted Kennedy, the bill never became law.

It’s time to try again, and not just in Congress. “A government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth,” Ronald Reagan once observed. If laws came with expiration dates, that would change. And lawmakers wouldn’t have to go to such lengths to repeal goofily obsolete laws about bug-deflectors and hen pheasants.