Citizens in the United States are usually proud of its constitutional system. After all, its conception of government was completely unique in the world, and Americans were responsible for creating written constitutions.

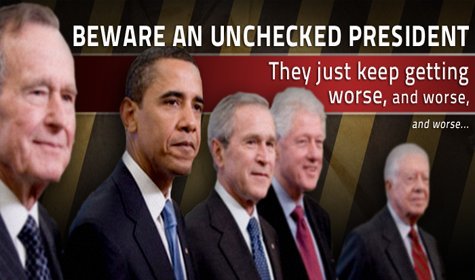

Still, modern government largely throws the constitutional system to the wind, adopting a political atmosphere more consistent with a monarchy than a republic. The modern presidency has assumed a higher level of authority than was imagined during the construction of the Constitution and ratification debates. As a result, the modern executive has more power than an 18th century king.

The founders came from a political system which did not grant kings unchallenged power. While many do not realize it, the authority of British Kings was often checked by vying power centers, and most kings did not actualize control over a state.

[slider id=’3303′ name=’ACNO Advertisements’ size=’full’]

In The Federalist #47, Madison wrote that “the magistrate in whom the whole executive power resides cannot of himself make a law.” Today, the president imposes new law in the form of executive orders, and binds citizens to his individual inclinations. He does not have the constitutional authority to do so, and often points back to his predecessors’ constitutional violations for justification.

When King John tried to bind England to his choice to lead the church through royal edict, he was forced by the sword to sign the Magna Carta which limited his rule.

Alexander Hamilton wrote that declaring war and the raising and regulating of fleets and armies would be a power that would “appertain to the legislature.” Today, the president makes unilateral war policy while considering Congress an afterthought. He sends troops and makes military strikes against foreign powers under his own volition, even at times when Congress is in recess.

When the actions of British King Charles I caused the Second English Civil War, the Parliamentarians responded with rage and eventually tried and executed him.

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “it would be thought a hard government that should tax its people one-tenth part of the time.” Today, the president proposes, levies, and enforces the tax code stringently through the Internal Revenue Service. As it is today, the Fourth Amendment restriction against unreasonable searches and seizures is continually violated through the collection of our personal information.

In the British constitutional system, the income tax was considered treacherous, unconstitutional, and detestable since King John tried to enact its first primitive form. Thus, the proclivity for government to tax income was a foreign idea to the founders.

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson charged King George III with creating “multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance.”

Today, the president creates a plethora of new offices, names “Czars,” and gives them power beyond the imagination of the founders. Today, they are involved in just about every aspect of our lives, from airport security, to agriculture, to education. They regularly invade our privacy, occupy our private property, and seize our earnings.

British history is filled with situations in which a monarch that acted like a current president was castigated, in ways much more strongly than the impeachment mechanism in Article II, Section 4 of our Constitution.

The only substantive way in which the English monarchs were more powerful than modern presidents was that their power was derived through hereditary inheritance. Nevertheless, contemporary presidents often establish new (often unconstitutional) federal officers with new advisors, and fill current ones with those loyal to his aims. These civil officers effectively extend his rule by enacting policy long after he is gone.

It has been a long road that has brought the office to this point, and is the result of several factors. Today, the Congress acts in a completely deferential role toward the president, refusing to try him for impeachment for fear that it may hurt their party. Party leaders sometimes make political deals with him, which allow him to continue behaving unconstitutionally. In the same way, the federal courts rarely check his power or restrain his agenda, and have the tendency to endorse consolidation of federal power. Largely, the president is inherently respected, whereas Madison suggested that he should be innately distrusted.

An executive official can exist without a written constitution, the British system proved that. The point of a written constitution is to define and limit the powers of the officeholders. Article II of the United States Constitution clearly calls for the office to have few powers, most of which are checked or controlled by the legislature. While explicit limitations are often ignored today, these confines should always be referenced by those who do not want to see an executive rule by decree. As patriots, we should be alarmed at the degree to which contemporary presidents have become modern kings.

Dave Benner speaks regularly in Minnesota on topics related to the United States Constitution, founding principles, and the early republic. He is a frequent guest speaker on local television and radio shows, and contributes writings to several local publications. Dave is the author of Compact of the Republic: The League of States and the Constitution.